Back in the 1960s, chemists searching for a tough, stable oxidant came across 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ). Curiosity and demand for more efficient organic transformations drove this quest. They wanted a tool to pull protons away from molecules in a controlled fashion, and DDQ rose up as a champion for this task. Its discovery and rollout changed the way scientists handled oxidation. Over the decades, as organic chemistry took off, DDQ stepped up in labs worldwide, especially as researchers sought cleaner and faster reactions.

Chemists keep DDQ on hand as a reliable oxidizing powerhouse. This compound comes in a yellow to orange crystalline solid form, easy to spot on a reagent shelf. It stands apart for its fierce electron-accepting grip, which lets it pull electrons off other molecules during reactions. This property explains why chemists see DDQ as a staple for oxidation, dehydrogenation, and aromatization processes. Being a small and robust molecule, DDQ often winds up as a go-to agent in labs focused on natural products, fine chemicals, and drug development.

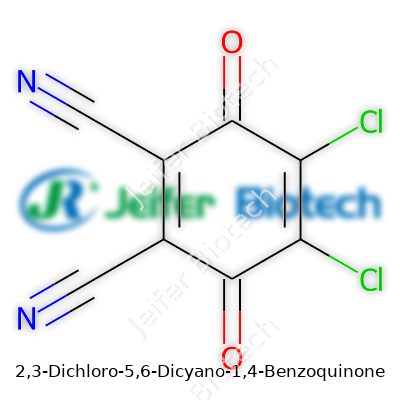

DDQ’s formula, C6Cl2N2O2, packs strength into a compact package with a molecular weight of about 227.99 g/mol. Its melting point ranges from 213–215°C, and exposure to sunlight or open air can shade its yellow hue toward darker tints. DDQ’s solubility hacks into acetonitrile or chloroform but avoids water, thanks to a lipophilic core. The dicyano and dichloro groups lend this molecule unmatched electron-withdrawing muscle, setting up strong interactions with organic substrates. DDQ releases pungent fumes if heated too much, and carelessness brings a sharp sting to the nose and eyes.

High-purity DDQ generally shows up at 98% or better grade in commercial bottles. Reputable suppliers publish shelf life data, storage advice (tight, amber bottles, cool and dry locations), and standardized batch specifics. Labels highlight strong oxidizing potential and hazard warnings—touch it with gloves, avoid inhalation, steer clear of ignition sources. Custom grades exist for higher-end applications in pharmaceuticals or research. Most labels give UN numbers, risk phrases, and the Globally Harmonized System’s hazard pictograms, with safety data sheets mandatory for handling and disposal details.

Manufacturing DDQ borrows lessons from classic quinone chemistry. Producers chlorinate 1,4-benzoquinone under controlled conditions before adding cyanide to attach cyano groups in just the right spots. Each step calls for solid technical oversight—uncontrolled temperatures or stray moisture spoil the outcome, stir up hazardous byproducts, or lead to batch decomposition. After workup and crystallization, DDQ needs repeated washing and drying cycles to hit the purity benchmark needed for sensitive synthetic work.

DDQ’s story doesn’t end with its basic structure. It’s a tool, and how it works in real reactions shows its depth. Chemists lean on DDQ to pull off dehydrogenation, snatch electrons during aromatization, and spark oxidation without strong acids or bases. In synthesis, DDQ helps convert alcohols to aldehydes or ketones, shift arenes into fully aromatic frameworks, and even break up overused protecting groups. It tolerates many functional groups, which gives it a flexible edge. There’s also a catalog of DDQ-derivatives engineered for fine-tuned reactivity in challenging transformations.

DDQ holds a mouthful of aliases across catalogs and papers: 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-p-benzoquinone, Chloranil dicyanide, and even its code numbers like NSC 97109. Laboratories and industry suppliers often streamline names to “DDQ” or drop the chemical prefixes entirely. This diversity in nomenclature led to mislabels or confusion, especially in cross-border trade, until international standards and CAS numbers took root in order systems.

Working with DDQ can never be taken lightly. Oxidants like this can cause burns and respiratory pain if handled carelessly. Even a seasoned chemist pays close attention to engineering controls—good ventilation, extraction hoods, closed systems. Eye wash stations and fire extinguishers stay within easy reach. Ingestion or skin contact calls for immediate flushing and medical oversight. Personal protective equipment isn’t optional. Disposal goes through specialized waste channels, because DDQ decomposes into toxic compounds if poured into the wrong waste stream. Environmental and safety regulators have set strict reporting and storage rules, which most chemical companies take seriously.

DDQ made its mark in total synthesis, fine-tuning chemical building blocks for medicines, dyes, and complex polymers. Pharmaceutical researchers rely on its ability to introduce or remove functional groups without lengthy pre-steps. Perfume and flavor makers use it during the controlled modification of aromatic rings, a nod to its mild yet effective oxidizing bite. Electronics and conductive polymer industries test DDQ in doping and electronic structure tuning, given its electron affinity. Academic labs see it as an educational tool, demonstrating redox chemistry and advanced organic transformations to graduate students tackling real-world projects.

Research hasn’t slowed down just because DDQ is old news. Molecule designers keep customizing benzoquinones for subtle changes in reactivity, trying to achieve even milder conditions or open yet-unknown synthetic possibilities. Green chemistry circles research recyclable versions or solid-supported DDQ analogs, which cut down on hazardous waste and streamline purifications. In drug discovery, scientists keep looking at DDQ’s reactivity to simplify synthesis, hoping to make medicines cheaper and production more sustainable. Coordination chemists even use DDQ as an electron-sink ligand, blending organic and inorganic fields.

Toxicology teams have spent serious lab hours tracing DDQ’s biological effects. Early animal studies pointed to organ damage at moderate doses and irritation on contact. Repeated exposure damages the liver and kidneys, with mutagenicity possible at high concentrations. This put DDQ on regulatory watchlists for safe use and encouraged periodic updates in handling advice. Chemists learned to work with small amounts, reinforce protection protocols, and test air for residues even after a reaction ends. Recent research keeps digging into chronic exposure, especially as demand rises in industry.

Demand for precise and selective oxidation will only climb as molecular targets in pharma, materials, and electronics get more complex. There’s room for DDQ evolution, either as a template to design safer, greener oxidants or as part of tandem-catalyst systems for process intensification. Ongoing trends push for minimal environmental impact; safer analogs, solid-supported forms, and recycling systems all look promising. DDQ’s core reactivity leaves a mark, yet the next chapters will focus on reducing hazards and broadening applicability without letting go of the reliability that earned it a spot in every advanced chemistry lab.

Anyone who has spent a few hours inside a chemistry lab has run into at least one chemical with a name like 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-Dicyano-1,4-Benzoquinone. Most folks shorten it to DDQ. Despite the intimidating label, DDQ marks a crossroads for both lab research and real world products—mainly because of its knack for pulling hydrogen atoms out of organic compounds. They call that dehydrogenation, but most days, it just means DDQ makes molecules more reactive or turns them into something useful.

In my own benchwork days, DDQ was the go-to for making benzylic alcohol turn straight into a benzaldehyde without much fuss. Its reactivity saves time. Scientists often count on DDQ in total synthesis, where they’re piecing together natural compounds, especially those tricky structures found in plants and drugs. If a team wants to recreate a painkiller or an antibiotic found in nature, odds are they’ll need at least one step only DDQ can handle cleanly. For example, it helps close carbon rings or build up complex backbones that other reagents burn or scramble.

It surprises some people, but DDQ leaves the lab and heads straight to factories. Its ability to tweak bonds without blowing up the rest of a molecule is valuable for pharmaceutical companies making certain drugs faster and with less waste. In electronics, DDQ comes up during the creation of organic semiconductors—used in OLED displays and some solar cells. By helping build and purify these specialty molecules, DDQ indirectly powers brighter screens and thinner devices.

Everything comes with trade-offs. DDQ brings efficiency but can pack some danger. It’s highly oxidizing, toxic if inhaled or swallowed, and can light up from static, making more than a few chemists nervous. Lots of labs handle it carefully behind fume hoods, double-gloving and checking fire extinguishers. The scale-up risks get tougher in mass production—waste, air emissions, and accidental releases matter more when trucks enter the picture rather than test tubes.

Given these risks, companies and research groups search constantly for alternatives. They try to invent new reagents that do the same job as DDQ but break down into less toxic byproducts or come from renewable sources. Green chemistry movements advocate for these replacements, offering incentives for safer and cleaner processes. Some teams even recycle DDQ right at the plant, recovering and purifying it to cut costs and limit pollution. Regulations already nudge toward less hazardous chemicals and demand proof that emissions and leftover solvents meet strict guidelines.

The world owes a fair bit to chemicals like DDQ. Progress in drug discovery, electronics, and synthetic biology sometimes hinges on that single, well-timed reaction it triggers. That said, people who use it rarely get complacent. Each gram measures out against both its utility and its hazards. I’ve had plenty of moments staring at the bottle, reminding myself why every step counts toward balancing science with safety. It’s a dance between achieving something impressive and respecting the fallout if you cut corners. With smarter management and safer substitutes, labs and factories can keep the good parts of chemicals like DDQ while cutting out unnecessary risk.

DDQ, short for 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone, stands out in organic chemistry as a powerful oxidizing agent. People like me who have spent hours in the lab appreciate what it can do, but also know it doesn't belong in just any hands. DDQ can damage skin, eyes, airways, and even lungs if ignored or underestimated. Following strict safety practices isn’t a choice—it's basic self-preservation in the world of chemistry.

Nobody should dive into a new experiment without reading the material safety data sheet (MSDS) for DDQ. The sheet explains real risks: how fast it irritates, at what point damage occurs, and what it does if inhaled or swallowed. MSDS documents serve as more than paperwork—they tell the ugly truth about contact burns, breathing problems, and even the risks of toxic byproducts released during careless heating. Solid preparation separates good chemists from lucky ones.

I never grab DDQ without proper gloves. Nitrile or heavy-duty latex is the go-to because this chemical eats through weak thin plastic the way lemons eat at cheap aluminum. Splash-proof goggles stay on the face from setup to cleanup. Skipping goggles is asking for permanent eye injuries—people don’t always realize that DDQ gets airborne faster than many expect, especially when handling or weighing the dusty yellow powder. A lab coat fastened tight keeps everything else from finding your skin. Sometimes a face shield helps too if a big batch is going or risk of splatter sits higher than usual. None of this is optional—it’s basic lab respect.

Even a quick whiff of DDQ can set the nose and lungs on fire. Always work with it in a certified fume hood. These hoods trap vapors and dust before they mix with room air. People who take shortcuts here endanger everyone in the building. I remember one scare back in grad school—a buddy of mine thought a cracked open window counted as ventilation. He coughed for days. Safety protocols protect not only the person handling the chemical but also the rest of us nearby.

DDQ needs tight, sealed containers kept far from light, heat, and moisture. Any leftover should be labeled—none of that “mystery bottle” nonsense. Spills deserve quick, focused attention. My routine: sweep up dry powder with a damp disposable cloth, bag everything (gloves and wipes included), and follow hazardous waste rules to the letter. Flushing it down the drain just spreads pollution downstream and puts municipal water folks at risk. Clear, documented disposal stops toxins from traveling where they don’t belong.

Lab work only stays safe with a culture that prizes diligence. Training new team members on DDQ’s seriousness can’t wait until the first accident, and a checklist at each station keeps folks honest. Routine audits work—catching outdated containers or sloppy labeling before accidents happen. Mistakes don’t need to turn into emergencies, and being strict about protective gear, air flow, and procedures lets everyone focus on the chemistry instead of constant worry over their own wellbeing.

Walk into any research lab that handles organic chemistry and you’ll probably find a jar labeled "DDQ" tucked away in a cool, dry spot. This compound, 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-Dicyano-1,4-Benzoquinone, holds a reputation for pushing electrons around, making it essential for certain oxidation reactions. But keeping it stable, safe, and effective isn’t just a matter of tossing it into any cabinet.

Get too casual with DDQ and trouble crops up fast. This isn’t just another powder. Direct sunlight, warmth, and a little bit of moisture can set off problems like decomposition or gas release. From my own hands-on work, I’ve seen a poorly capped bottle start clumping and turning color. That batch lost its punch, wasting not only chemical but also precious hours of work.

Most stockrooms use amber bottles with tight-sealing lids for good reason. DDQ reacts with light and picks up water from the air. Keeping it dry stops dangerous hydrolysis. A desiccator will provide an extra measure of confidence, especially if your local climate runs humid.

Temperature stays just as important. Refrigerators work well as long as containers stay sealed. DDQ doesn’t handle freezing temperatures—stay above zero Celsius to avoid changes in crystal structure. Skip the freezer, stick to cool storage.

Anyone who’s handled enough samples knows accidents can crop up from simple forgetfulness. Forget to recap a jar? You’ll pick up that unmistakable acrid odor, signaling that fresh DDQ’s losing its edge. Spilled powder can irritate eyes and airways. Solid chemical precautions aren’t about following the book; they keep people healthy and budgets intact.

Always use gloves and goggles. Lab coats might feel overkill in a quiet storage room, yet a quick slip or spill with DDQ leaves skin stains and lasting irritation. It’s a sharp reminder—good habits beat regrets every time.

Sharp labels and up-to-date logs make all the difference. Freshness dates and hazard symbols cut down on mistakes, especially if new team members join the lab. Rotate older containers forward, just like food in a pantry. Small steps like these prevent confusion and wasted money.

Forget fancy buzzwords; just trust the basics. Store DDQ in a light-blocking, sealed container. Keep it cool but above freezing. Toss a desiccant pack in if moisture’s a risk. Wear gloves, close lids, and document batch ages. Pay attention to safety data sheets, and don’t keep more than you can use within a year.

I’ve relied on these habits both as a student and leading a small research group. Careful storage turned DDQ from a hazard into an everyday tool—one that’s powerful but safe when treated right. Thoughtful, practical steps build trust and save time for the real work that moves science forward.

DDQ stands for 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone. Its chemical formula, C8Cl2N2O2, might look intimidating on paper, but the molecule itself has a straightforward and memorable structure. The name says a lot: two chlorines at positions 2 and 3, two cyano groups at positions 5 and 6, built on a benzoquinone skeleton. This molecule’s structure lets it take electrons away from other compounds, making it a go-to oxidizing agent for chemists, especially in organic synthesis and the lab bench world.

Years of grubbing around in the lab taught me the value of a chemical that delivers results—a ‘heavy lifter’ reagent. DDQ fits this bill. With its rigid, aromatic core and four potent substituents, it behaves in a way that shifts reactions into high gear. For example, DDQ helps remove hydrogen atoms from certain molecules, a crucial step in making drugs, dyes, and materials for electronics. This direct, robust action means researchers spend less time troubleshooting side-reactions and more time building the molecules they need.

The punch DDQ packs comes straight from its chemical makeup. The two chlorine atoms and two cyano groups pull electrons into the quinone ring, creating a powerfully electron-deficient system. This layout invites molecules to give up their electrons, often transforming them in the process. DDQ’s oxidizing talent draws from this fine-tuned balance—enough backbone to stay stable on the shelf, sharp reactivity when mixed with the right substrate.

Anyone who’s used DDQ knows it is more than just a chemical formula—it brings risks. It can irritate the skin, eyes, and respiratory tract. The disposal of DDQ and its byproducts needs special care; its chlorinated and nitrile-loaded backbone doesn’t break down easily. Getting exposed to DDQ’s yellow dust once taught me to respect boundaries: gloves, goggles, and keeping reactions under the fume hood. Lab managers and researchers need safe handling protocols and proper waste management to limit environmental impact. The push for greener chemistry means looking for alternatives or improved methods that use less aggressive oxidants, or ways of recycling DDQ after use.

Sustainable chemistry isn’t just a buzzword; it’s a real aim in labs around the world. Several teams are working to find substitutes that achieve the same results DDQ delivers, but with lower toxicity and safer breakdown products. Others are changing reaction setups to minimize the amount of reagent needed, or designing systems where DDQ gets regenerated through electrochemistry. In a teaching lab, I’ve seen students learn not just synthesis, but also the value of risk assessment and thoughtful cleanup—important steps in building a responsible research culture.

Each time a chemist turns to DDQ for a synthesis challenge, that choice touches issues of safety, efficiency, and sustainability. Keeping an eye on its structure and formula does more than inform a lab manual—it shapes decisions that ripple from chemistry benches to materials manufacturing and drug development. Knowing the ins and outs of DDQ’s molecule isn’t about trivia; it’s about accountability, progress, and a smarter use of resources.

Every time I’ve handled 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-Dicyano-1,4-Benzoquinone (or DDQ, as most chemists call it), one thought crosses my mind: this isn’t the sort of compound you want to take lightly. In synthetic labs, DDQ stands out for its use as an oxidizing agent, breaking molecular bonds to help researchers build new drugs or advanced materials. Its usefulness nearly matches its reputation for being hazardous, and for good reason.

I remember a safety briefing during grad school: the instructor made a point to tell us that DDQ irritates skin and eyes, and inhaling its dust causes nasty respiratory issues. This isn’t just theory. Published toxicity data show that DDQ can harm lungs if inhaled, and the compound damages mucous membranes on contact. It doesn’t just irritate; it burns. Skin exposure brings out redness and pain, while a spill left unattended can damage tissue.

DDQ carries an LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of tested mice) of about 60 mg/kg, according to the National Library of Medicine. Researchers consider anything with an LD50 below 200 mg/kg quite toxic. Most lab manuals warn not to risk even small exposures—this stuff deserves respect.

Though DDQ doesn’t ignite easily, if a fire does start, this compound releases dangerous gases: hydrogen chloride, dicyanogen, phosgene—each with a toxic history. I once watched firefighters enter a university facility after someone dropped a vial during a small-scale production run. The real panic came not from the flames, but from the chemical vapors. Toxic fumes travel fast in enclosed spaces, so a tiny spill can quickly become a big hazard for an entire building.

Its toxic profile extends beyond the person handling it. Disposal brings another headache. Waterways can’t tolerate DDQ; even in small doses, aquatic life suffers. Many environmental safety agencies flag it for careful waste management. No one wants to see rivers near research centers show higher concentrations of dicyano compounds, since these linger in water, harming fish and plants for weeks.

Training goes a long way. Before I even opened my first bottle of DDQ, my supervisor made me recite safe handling rules. Gloves, full lab coat, sealed goggles, and a well-ventilated fume hood aren’t suggestions—they’re requirements. Dedicated spill kits should always stay within arm’s reach, and every lab tech needs to know where they’re stored.

Disposal requires more than tossing used solutions down the drain. Every drop of leftover DDQ heads to labeled hazardous-waste containers, where certified staff manage it according to federal and state laws. Facilities invest in regular training sessions, because regulations for chemicals like DDQ change as scientists learn more about their effects on people and the planet.

Green chemistry — the search for safer alternatives — remains on the agenda. Some research groups experiment with milder oxidants or improve reaction efficiency to cut waste. Until then, I believe every lab using DDQ must treat it with the same care they’d give any legacy hazardous material. Safe storage, clear communication, and strict handling protocols keep researchers, cleaners, and neighbors safe.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione-1,4-dicarbonitrile |

| Pronunciation | /ˈtuːθriː daɪˈklɔːrəʊ faɪvˈsɪks daɪˈsaɪənoʊ wʌnˈfɔːr bɛnzoʊkwɪˈnoʊn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione-1,4-dicarbonitrile |

| Pronunciation | /ˌdiː.kloʊˌdaɪˈsaɪ.ə.noʊˌbɛn.zoʊ.kwɪˈnoʊn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 84-58-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 120873 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:53070 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL155488 |

| ChemSpider | 5887 |

| DrugBank | DB08625 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03f0d2e6-3957-46f6-b6e6-2fe9550a8f0e |

| EC Number | 206-703-1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 76643 |

| KEGG | C01821 |

| MeSH | D003707 |

| PubChem CID | 85737 |

| RTECS number | KV5775000 |

| UNII | 29NC68V353 |

| UN number | UN3347 |

| CAS Number | 84-58-2 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `load =3d7q` |

| Beilstein Reference | 1911250 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:39054 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1409 |

| ChemSpider | 6785 |

| DrugBank | DB08280 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03d75f45-10cc-49f5-b713-1fd0af6f0b40 |

| EC Number | 208-960-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin 180157 |

| KEGG | C10448 |

| MeSH | D03.438.221.173.171 |

| PubChem CID | 8612 |

| RTECS number | KH7875000 |

| UNII | L5M10FQS5N |

| UN number | UN2588 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | urn:uuid:d4b68723-3fbc-41e4-89e4-0fcdf9e8a4a5 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6Cl2N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 227.93 g/mol |

| Appearance | Red to dark red crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.7 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 2.7 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | 1.82 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.0025 mmHg (25 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | -0.21 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb = 6.57 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -37.6·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.545 |

| Viscosity | 5.44 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.30 D |

| Chemical formula | C6Cl2N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 227.03 g/mol |

| Appearance | Red crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.68 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | sparingly soluble |

| log P | 1.67 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.0025 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | -0.03 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 18 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -38.7·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.545 |

| Viscosity | 2.65 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.61 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 227.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −145.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -840 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 340.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -225.8 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -962 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes skin irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H312 + H332: Harmful if swallowed, in contact with skin or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P261, P273, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2,3,2,0 |

| Flash point | 93 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 305 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat) 230 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 190 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | DJ3675000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.01 ppm |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes skin irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Suspected of causing genetic defects. Toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS06, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302, H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P330, P337+P313, P362+P364, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2,3,2,0 |

| Flash point | 87 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 300 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 84 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 190 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SG1400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.01 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |